Why Make Personal Social Issue Films?

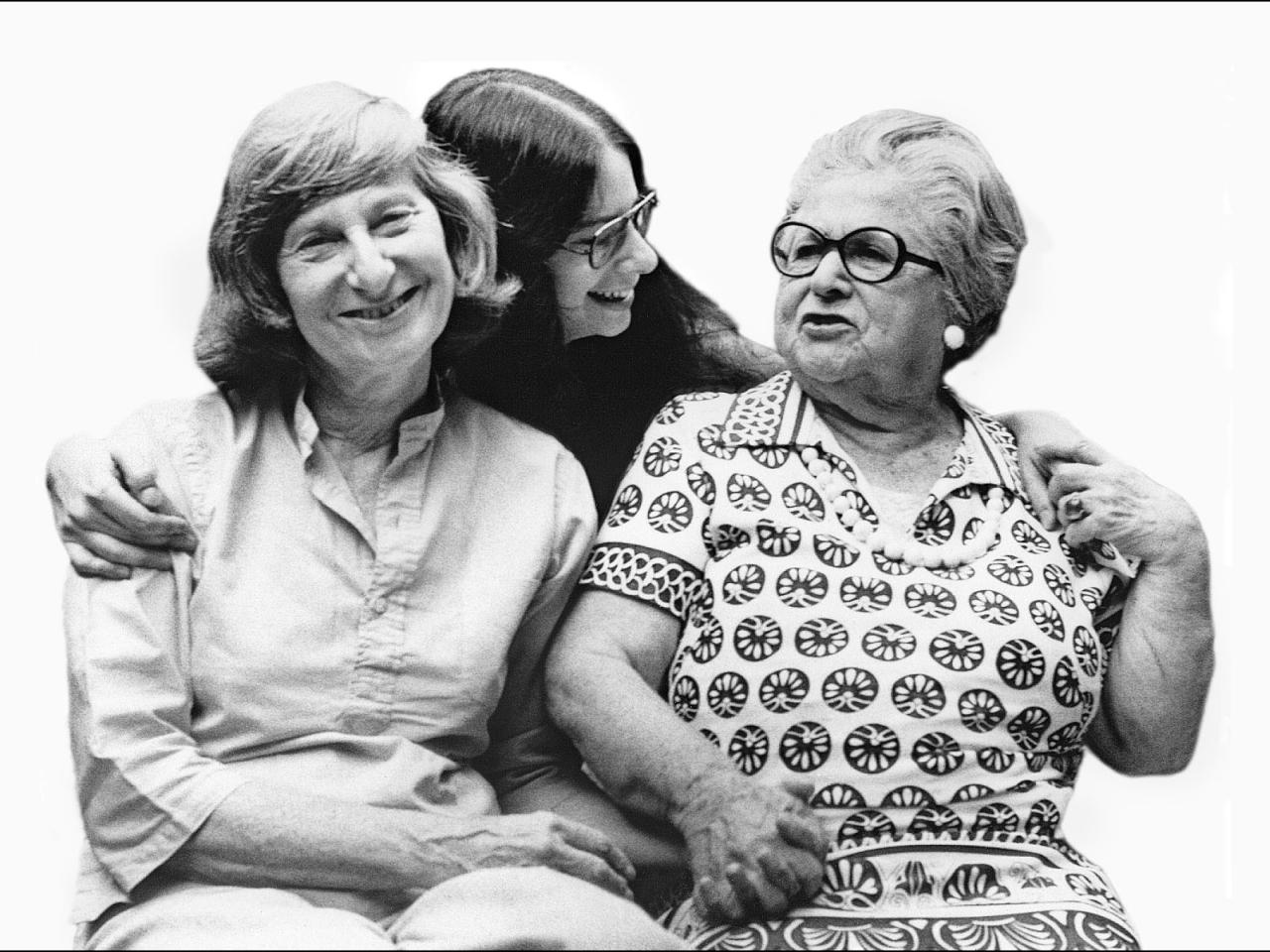

One of the films that touched me as a young woman is Amalie Rothschild’s Nana, Mom and Me. Today it is a classic film; in the seventies it broke new ground.

Using photographs, old home movies and direct interviews with her mother and grandmother as well as herself, Rothschild explores the mother-daughter ties in three generations of her own family. In the process she explores the classic female problem faced by her artist mother: the conflict between work and children - the necessary compromises, the incumbent anxieties. The structure is intentionally loose and open-ended, like a good conversation, emphasizing the need to ask the right questions rather than give pat answers. Recently I watched Rothschild’s film again, this time as a mother struggling with many of the same issues nearly four decades after the film was made. Returning to the film I thought about how the first-person approach has persisted and evolved over the decades. According to the American University Center for Social Media, “Personal essay films are particularly good at dramatizing the human implications and consequences of large social forces.”

I spoke with several New Day filmmakers who included themselves on-screen, and found many didn’t set out to include themselves in their films. Some found themselves taking a first-person approach for strategic reasons. In the film By Invitation Only, about the elite, white Carnival societies and debutante balls of Mardi Gras, director Rebecca Snedeker started working with cinema verite footage and interviews. Over time, though, she realized that, “I had questions that I wanted the film to explore that we could not clearly address through my central character. The first-person narrative allowed us to tease out topics, to gently ask questions and offer reflections. These debutante and carnival traditions are such a foreign, mysterious world to most people, even here in New Orleans, and images of them conjure immediate assumptions and prejudices; just showing the observational footage I was able to capture probably wouldn’t have moved many viewers to a new place, or inspire them to consider the push and pull of other traditions and status quo situations in their own lives.”

Similarly, Kelly Anderson decided to put her own story, as a Brooklyn "gentrifier," into My Brooklyn after she had been editing the film for several years. “I was worried it would be too self-indulgent - another filmmaker in her own movie? Please!" she says. But her perspective, as a white person who was concerned with issues of racial and economic equality, but who had also been part of demographic change in formerly Black or Latino neighborhoods, proved a good entry point for many viewers. “In the end, it was about making a policy-dense film feel more approachable and interesting, and also about the ethics of representing others in a situation you are a part of, and how to do that honestly,” Anderson says.

When she moved to Alaska, vegetarian Ellen Frankenstein was confronted with new eating challenges, and decided to make a film about it. “I wanted to make an environmental film focused on food, but I didn't want to point fingers or do it in a simple style,” Frankenstein says. “I didn't set out to be in Eating Alaska. I put myself in the film as the provocateur, on a journey to figure out what made sense to eat. It has been a great tool for allowing audiences to talk about the choices they make everyday.”

Some of the most compelling reasons filmmakers put themselves into their own films are ethical. In the case of Dan Lohaus, whose film When I Came Home is about homeless veterans on the hard streets of New York City, it was his own sense of humanity that drove him to “cross the line” and include himself. When his lead character Herold contemplates suicide as winter sets in, the filmmaker allows him to sleep on his couch. When Dan steps in front of the camera and has to invite a buddy in to film the turn of events, the objective relationship is altered, as is the film’s style and structure.

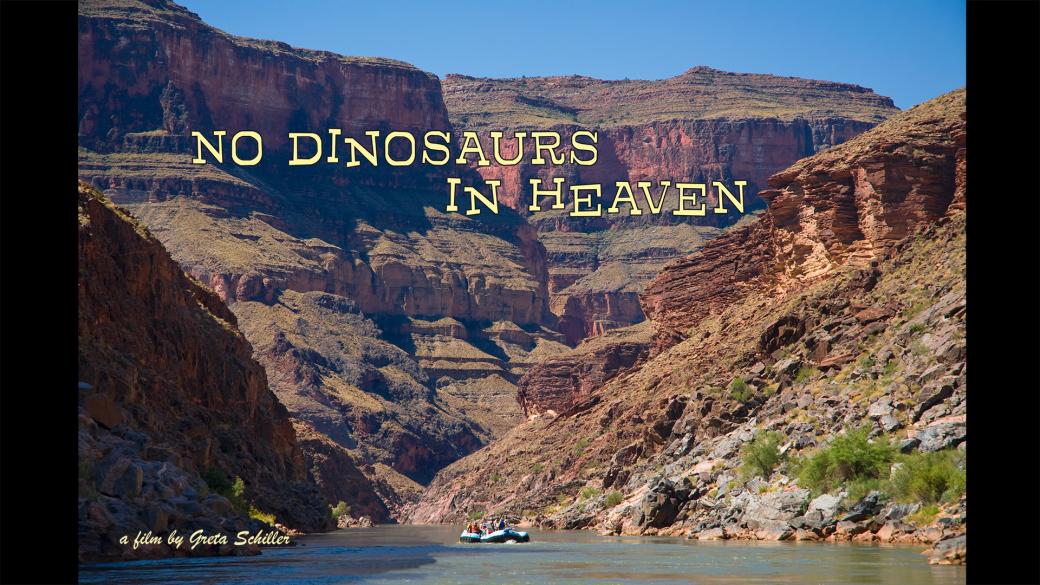

There are a million stories in New York, and the third one I will mention is my own film No Dinosaurs In Heaven. I was also hesitant to include my image and voice-over, but I felt it was dishonest not to let the audience know that I was in fact a student in the biology class of the creationist professor. I felt his behavior was dishonest, and that I needed to be very up front about my relationship to him and to the topic of creationism. No film had ever attempted to diagram the way an individual can manipulate liberal educational philosophy into a tolerance for creationism in the science classroom. It was my point of view that a creationist could not teach science, and in fact he was deliberately hiding his anti-science belief to promote religion.

Some filmmakers find the power relations inherent in documentary filmmaking reversed when their subjects draw them into the filmmaking process. Asian American filmmaker Debbie Lum began work on Seeking Asian Female intending to make an objective film about men who are obsessed with Asian women. “The original idea was to turn the tables on these men and make an objective film about their objectification of Asian women,” Lum says. But when the main character in her film found a woman in China who was half his age to come live with him in San Francisco, she found herself in an unexpected position. “As I filmed and sparks flew, they began to lean on me to translate and my role morphed from documentary observer to marriage counselor. The journey that all three of us went on was full of unexpected lessons, not the least of which was that we all had quite ingrained stereotypes that we had to confront as we got to know each other more personally.”

The family is the most obvious choice for personal stories in social issue films and New Day has several deeply personal and daringly intimate films. In Father’s Day, Mark Lipman uses evocative home movies and poetic imagery to immerse viewers in conversations about death, suicide, mental illness, memory and the choices we make in creating a family. In Sunshine, Karen Skloss explores the meaning of family through her own journey to understand the legacy of her own birth and the nontraditional family she created by co-parenting with her ex-boyfriend. “These kinds of films hold great risk of being self-indulgent,” Skloss says. “But I thought that if it were honest enough and went deeply enough that it would resonate for an audience and open up a lot of areas for conversation - which it has.” Unlike Reality TV or programming strands that rely on formulaic story structure - usually two central characters on either side of an issue - New Day embraces many storytelling devices. This makes our collection both strong in its diversity and evergreen as we delve deeply and sometimes personally into the zeitgeist of our times.